Arapaho National Forest

| Arapaho National Forest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Fort Collins, CO |

| Coordinates | 39°35′19″N 105°38′34″W / 39.588611°N 105.642778°W |

| Area | 723,744 acres (2,928.89 km2) |

| Established | July 1, 1908 |

| Governing body | U.S. Forest Service |

| Website | Arapaho & Roosevelt National Forests and Pawnee National Grassland |

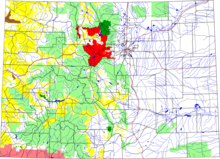

Arapaho National Forest is a National Forest located in north-central Colorado, United States. The region is managed jointly with the Roosevelt National Forest and the Pawnee National Grassland from the United States Forest Service office in Fort Collins, Colorado. It has a wildlife refuge which manages a protection for all birds and mammals. The combined facility of 1,730,603 acres (7,004 km2) is denoted as ARP (Arapaho, Roosevelt, Pawnee) by the Forest Service. Separately, Arapaho National Forest consists of 723,744 acres (2,929 km2).[1]

The forest is located in the Rocky Mountains, straddling the continental divide in the Front Range west of Denver. It was established on July 1, 1908, by President Theodore Roosevelt and named for the Arapaho tribe of Native Americans which previously inhabited the Colorado Eastern Plains. The forest includes part of the high Rockies and river valleys in the upper watershed of the Colorado River and South Platte River. The forest is largely in Grand and Clear Creek counties, but spills over into neighboring (in descending order of land area) Gilpin, Park, Routt, Jackson, and Jefferson counties. There are local ranger district offices located in Granby and Idaho Springs.

Wilderness areas

[edit]There are six officially designated wilderness areas within Arapaho National Forest that are part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. Four are partially in neighboring National Forests, and one also extends onto National Park Service land:

- Byers Peak Wilderness, 13.93 square miles

- Indian Peaks Wilderness, 119.9 square miles (partly in Roosevelt NF; also partly in Rocky Mountain National Park)

- James Peak Wilderness, 26.59 square miles (mostly in Roosevelt NF)

- Mount Evans Wilderness, 116.3 square miles (partly in Pike NF)

- Never Summer Wilderness, 32.95 square miles (partly in Routt NF)

- Vasquez Peak Wilderness, 19.22 square miles

Wildlife

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

The ponds also produce many insects and other invertebrates needed by most female waterfowl for successful egg laying. These insects also serve as an essential food item for the growth of ducklings and goslings during the summer months.

The first waterfowl arrive in the spring when the ice vanishes in April. The peak migration occurs in late May when 5,000 or more ducks may be present. Canada geese have been reestablished in North Park and begin nesting during April. Duck nesting usually starts in early June and peaks in late June. The forest produces about 9,000 ducklings and 150 to 200 goslings each year. The Fish and Wildlife Service expects that when refuge lands are fully acquired and developed, waterfowl production should increase significantly.

There have been 198 bird species recorded in the forest.[2] Primary upland nesting species include the mallard, pintail, gadwall, and American wigeon. A number of diving ducks, including the lesser scaup and redhead, nest on the larger ponds and adjacent wet meadows. Most species may be observed during the entire summer season. Fall migration reaches its height in late September or early October when up to 8,000 waterfowl may be present.

The wetlands also attract numerous marsh, shore, and water birds. Sora and Virginia rails are numerous but seldom seen. If they are present, Wilson's phalarope, American avocet, willet, sandpipers, Greater yellowlegs, and dowitchers will be easy to observe. Other less common species include great blue heron, black-crowned night heron, American bittern, and eared and pied-billed grebe.

The upland hills harbor sage grouse year around with a winter population of more than 200 birds. Golden eagles, several species of hawks, and an occasional prairie falcon circle the skies above in search of food. Their prey includes Richardson's ground squirrel, white-tailed prairie dog, and white-tailed jackrabbit.

Badger, muskrat, beaver, coyote, and pronghorn are commonly observed. It is also possible to see a raccoon, red fox, mink, long-tailed weasel, or porcupine. As many as 400 mule deer have wintered here and up to 200 elk are frequently seen during the winter months. Moose have recently been reintroduced into North Park and may occasionally be observed in the willow thickets along the Illinois River bottoms. There are no venomous snakes anywhere in this forest.

Wildfires

[edit]The Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests were affected by five major wildfires (Cameron Peak, East Troublesome, Williams Fork, Lefthand Canyon and CalWood) in 2020, burning over 25% of their total lands.[3] The Williams Fork Fire was the largest wildfire Arapaho National Forest had ever experienced until it was surpassed by the East Troublesome fire 2 months later.[4]

As of 2024, the US Forest Service is continuing to work on long-term recovery, including reforestation, stream and waterway repair, fixing road and trail damage, repairing fences between range allotments, repairing historic buildings, and identifying and treating noxious weeds within the fire footprints.[3] In 2023, 344,000 seedlings were planted across 1,800 acres of high burn severity forest.[3]

In popular culture

[edit]Most of the movie Red Dawn is set in Arapaho National Forest.

The Arapaho National Forest plays a significant role in Laurell K. Hamilton's Affliction (part of the Anita Blake book series).

The Grizzly West region of the video game Red Dead Redemption 2 is heavily based on the Arapaho National Forest.

References

[edit]- ^ "Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County". US Forest Service. September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008.

- ^ "Arapaho National Wildlife Refuge". USGS. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c "2020 Fire Recovery Information". US Forest Service. Archived from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ "Williams Fork Fire responders and partners reflect one year later". US Forest Service. August 14, 2021. Archived from the original on April 15, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests and Pawnee National Grassland (United States Forest Service)

- ColoradoGuide.com Archived 12 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Arapaho National Forest

- National Forests of Colorado

- National Forests of the Rocky Mountains

- Protected areas of Clear Creek County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Gilpin County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Grand County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Jefferson County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Park County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Routt County, Colorado

- Protected areas of Summit County, Colorado

- Protected areas established in 1908

- 1908 establishments in Colorado