Ana Castillo

Ana Castillo | |

|---|---|

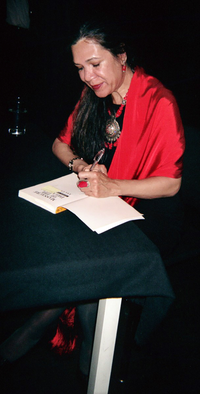

Ana Castillo in New Mexico | |

| Born | June 15, 1953 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Jones Commercial High School Northeastern Illinois University (BS) University of Chicago (MA) University of Bremen |

| Literary movement | Xicanisma / Postmodernism |

| Notable works | So Far from God, Massacre of the Dreamers, Loverboys, The Guardians |

| Notable awards | Columbia Foundation's American Book Award (1987) |

Ana Castillo (born June 15, 1953) is a Chicana novelist, poet, short story writer, essayist, editor, playwright, translator and independent scholar. Considered one of the leading voices in Chicana experience, Castillo is most known for her experimental style as a Latina novelist and for her intervention in Chicana feminism known as Xicanisma.[1][2]

Her works offer pungent and passionate socio-political comment that is based on established oral and literary traditions. Castillo's interest in race and gender issues can be traced throughout her writing career. Her novel Sapogonia was a 1990 New York Times Notable Book of the Year,[3] and her text So Far from God was a 1993 New York Times Notable Book of the Year.[4] She is the editor of La Tolteca, an arts and literary magazine.[5]

Castillo held the first Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Endowed Chair at DePaul University. She has attained a number of awards including a 1987 American Book Award[6] from the Before Columbus Foundation for her first novel, The Mixquiahuala Letters, a Carl Sandburg Award, a Mountains and Plains Booksellers Award, a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in fiction and poetry and in 1998 Sor Juana Achievement Award by the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum in Chicago.[7]

Life and career

[edit]Castillo was born in Chicago in 1953, the daughter of Raymond and Rachel Rocha Castillo.[8] Her mother was Mexican Indian and[9] her father was born in 1933, in Chicago.[10] She attended Jones Commercial High School and Chicago City Colleges before completing her BS in art, with a minor in secondary education, at Northeastern Illinois University.[8][11] Ana Castillo received her MA in Latin American Studies from the University of Chicago in 1979, after teaching ethnic studies at Santa Rosa Junior College and serving as writer-in-residence for the Illinois Arts Council.[8] She has also taught at Malcolm X Junior College and later on in her life at Sonoma State College.[10][11] Ana Castillo received her doctorate from the University of Bremen, Germany, in American Studies in 1991.[8] In lieu of a traditional dissertation, she submitted the essays later collected in her 1994 work Massacre of the Dreamers.[8] Castillo, who has written more than 15 books and numerous articles, is widely regarded as a key thinker and a pioneer in the field of Chicana literature.[11] She has said, "Twenty-five years after I started writing, I feel I still have a message to share."[10]

Castillo writes about Chicana feminism, which she refers to as "Xicanisma," and her work centers on issues of identity, racism, and classism.[1] She uses the term "xicanisma" to signify Chicana feminism, to illustrate the politics of what it means to be a Chicana in our society, and to represent the Chicana feminism that challenges binaries regarding the Chicana experience such as gay/straight black/white. Castillo writes, "Xicanisma is an ever present consciousness of our interdependence specifically rooted in our culture and history. Although Xicanisma is a way to understand ourselves in the world, it may also help others who are not necessarily of Mexican background and/or women. It is yielding; never resistant to change, one based on wholeness not dualisms. Men are not our opposities, our opponents, our 'other'".[12] She writes, "Chicana literature is something that we as Chicanas take and define as part of U.S. North American literature. That literature has to do with our reality, our perceptions of reality, and our perceptions of society in the United States as women of Mexican descent or Mexican background or Latina background".[13] Castillo argues that Chicanas must combat multiple modes of oppression, including homophobia, racism, sexism and classism, and that Chicana feminism must acknowledge the presence of multiple diverse Chicana experiences.[14] Her writing shows the influence of magical realism.[11] Much of her work has been translated into Spanish, including her poetry. She has also contributed articles and essays to such publications as the Los Angeles Times and Salon. Castillo is the editor of La Tolteca, an arts and literary magazine.[15]

She was also nominated in 1999 for the "Greatest Chicagoans of the Century" sponsored by the Sun Times.[10]

Her papers are housed at the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Poetry

[edit]As a poet Castillo has authored several works, including Otro Canto (1977), The Invitation (1979), Women Are Not Roses (Arte Publico, 1984), and My Father Was a Toltec (West End Press, 1988).[16] Her works primarily communicate the meaning and revelations we discover in various experiences. Her poem, "Women Don't Riot," explores the tribulations of womanhood, but Castillo daringly uses the lines of this poem as her "offense, rejection" (line 49–50 of the poem) of the idea that she will sit quiet.[citation needed]

She often intermingles Spanish and English in her poetry, like in her collection of poems entitled I Ask the Impossible. The hybrid of languages that she creates is poetic and lyrical, using one language to intrigue another as opposed to a broken "Spanglish".[citation needed]

Bibliography

[edit]

Novels

[edit]- The Mixquiahuala Letters. Binghamton, N.Y. : Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingue, 1986. ISBN 0-916950-67-0

- Sapogonia: An anti-romance in 3/8 meter. Tempe, Arizona: Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe, 1990. ISBN 0-916950-95-6

- So Far from God. New York: W. W. Norton, 1993. ISBN 0-393-03490-9

- Peel My Love Like an Onion. New York: Doubleday, 1999. ISBN 0-385-49676-1

- My Daughter, My Son, the Eagle the Dove: An Aztec Chant. New York: Dutton Books, 2000. ISBN 0-525-45856-5

- Watercolor Women, Opaque Men : A Novel in Verse. Willimantic, Connecticut: Curbstone Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-931896-20-7

- Give It to Me. New York: Feminist Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-55861-850-3

- The Guardians. New York: Random House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4000-6500-4

The Guardians

[edit]Summary

[edit]The Guardians is one of Castillo’s most noteworthy pieces of work. As a resident of New Mexico an obvious political, social, and cultural issue was happening in her vicinity at the border. The Guardians addresses the perpetual crimes innocent people face who are looking for a better life on the other side, or as Castillo says, “el otro lado.”

The Guardians is a story about Regina, who is raising her nephew, Gabo in El Paso, Texas. Regina's brother, Rafa, crosses back to Mexico to be with Gabo's mother, Ximena. When they attempt to cross the border together, Ximena and Rafa were separated. Soon after, Ximena's body was found and she was mutilated with her organs removed. When Gabo’s father, Rafa, has gone missing after attempting to cross the border, Regina and Gabo seek solace in their own ways and support from classmates and colleagues. Gabo is very religious, and aspires to be a priest when he is older. He is a top student who embodies high morals and yearns to live a happy life on the U.S. side of the border. When his thoughts think the worst, he gets involved with a gang, Los Palominos, in hopes that they can help find his missing father.[17] On Regina’s end, she teams up with a colleague Miguel and his grandfather, Milton. When Miguel’s ex-wife is kidnapped, all characters team up to find their missing loved ones. In the end, Miguel finds his ex-wife alive who was also found with Tiny Tears, and both were in dire shape. On the other hand, Regina and Gabo’s instincts that the worst occurred, came true, as Rafa was found dead in a house belonging to Los Palominos. That same night, Gabo was killed by Los Palominos member, Tiny Tears, who was initially helping Gabo in his quest to find his father.[18]

Analysis

[edit]Castillo’s writing about the novel proves to be straightforward yet explained creatively while always keeping in mind her duty to make readers aware of the current events at the border. This novel uncovers the truths about life on both sides of the border for Mexican immigrants. On one hand, many people and families migrate to the United States so they can receive a better education and find better jobs. Conversely, the United States does not feel like home for many migrants and yearn for reunification with family members. They are conflicted between where they feel they belong and opportunities. This exact reason is why Rafa returns to Mexico after already having crossed the border.[19]

Criminal organizations, commonly referred to as the cartels, smuggle all kinds of goods across the border.[20] Cartel members do not see migrants not as humans, but rather just a small piece of their many smuggling operations.[21] In Mexico, migrants cannot cross themselves. The U.S. has militarized the border, making it a dangerous territory.[22] Consequently, criminal organizations involved in human smuggling are able to capitalize on this, making human smuggling across the border a lucrative business. Instead, they must pay a coyote to get them across. If they tried to do it themselves, they could face serious consequences from the criminal organizations and narcotraficantes that “own” the borderlands.[23]

As a result, these criminal activities are informally engrained in the economy of the towns and communities living near the border. Thus, when Gabo and Regina fear the worst, it is not difficult for them to find a cartel association who may have information. The approach in which Abuelo Milton uses to look for Rafa is walking the streets with his dog and questioning pedestrians. These examples display the typical nature of these circumstances for families on the border.

Main Themes

[edit]Violence Against Women

[edit]Castillo addresses the crimes that people living in border towns may be subjected to.[24] Specifically, crimes against women. Ximena's death, the kidnapping of Miguel's ex-wife, and the life story of Tiny Tears are all representative of border violence against women.

When women cross the border, sexual violence is not uncommon. Already in a vulnerable state, men and cartel members take advantage of the circumstance.[25] As a result, women living by the border or immigrants trying to cross are subjected to such violence. Additionally, these crimes have psychological effects that can cloud one's judgment or influence behavior. In The Guardians, Tiny Tears yearns for family and other forms of bonds to fill the voids in her life. as a result of violence. Consequently, she looks for family in a criminal sense, by joining Los Palominos.

Chicano Culture

[edit]Castillo not only addresses the common horror stories, but also addresses the cultural implications of what it means to be Mexican but live in the United States.

To illustrate this, Castillo accentuates Regina’s experiences on both sides of the border. On one hand, Regina has experienced the hardships that many Mexican people and migrants endure, such as picking crops or partaking in manual labor that is bodily taxing.[26] However, when she immigrated and worked to become a teacher’s aide, she is no longer in the same boat as many of her confidantes. One may internalize this new experience and feel conflicted between where they came from versus their new way of life. In turn, feelings of betrayal and isolation for some may arise. For others, remembering past experiences or holding onto the stories of close ones can be a source of strength.[27] For Regina, her life as a teacher’s aide is refreshing; although, people like her brother Rafa and their circumstances will always stick with her.[28]

Story collections

[edit]- Loverboys. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996. ISBN 0-393-03959-5

Poetry

[edit]- Otro Canto. Chicago: Alternativa Publications, 1977.

- The Invitation. 1979

- Women Are Not Roses. Houston: Arte Público Press, 1984. ISBN 0-934770-28-X

- My Father Was a Toltec and selected poems, 1973–1988. New York: W. W. Norton, 1995. ISBN 0-393-03718-5

- I Ask the Impossible. New York: Anchor Books, 2000. ISBN 0-385-72073-4

- "Women Don't Riot"

- "While I was Gone a War Began"

Non-fiction

[edit]- black dove: mamá, mi'jo, and me. New York City: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2016. ISBN 9781558619234 (paperback)

- Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8263-1554-2

Translations

[edit]- Esta puente, mi espalda: Voces de mujeres tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos (with Norma Alarcón). San Francisco: ism press, 1988. (Spanish adaptation of This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga.)

As editor

[edit]- The Sexuality of Latinas (co-editor, with Norma Alarcón and Cherríe Moraga). Berkeley: Third Woman Press, 1993. ISBN 0-943219-00-0

- Goddess of the Americas: Writings on the Virgin of Guadalupe / La Diosa de las Américas: Escritos Sobre la Virgen de Guadalupe (editor). New York: Riverhead Books, 1996. ISBN 1-57322-029-9

Bibliographical Resources

[edit]https://faculty.ucmerced.edu/mmartin-rodriguez/index_files/vhCastilloAna.htm

See also

[edit]Critical studies since 2000 (English only)

[edit]Journal articles

[edit]- Castillo's 'Burra, Me', 'La Burra Mistakes Friendship with a Lashing', and 'The Friend Comes Back to Teach the Burra' By: Ruiz-Velasco, Chris; Explicator, 2007 Winter; 65 (2): 121–24.

- 'The Pleas of the Desperate': Collective Agency versus Magical Realism in Ana Castillo's So Far From God By: Caminero-Santangelo, Marta; Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, 2005 Spring; 24 (1): 81–103.

- Violence in the Borderlands: Crossing the Home Space in the Novels of Ana Castillo By: Johnson, Kelli Lyon; Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 2004; 25 (1): 39–58.

- Literary Syncretism in Ana Castillo's So Far From God By: Alarcón, Daniel Cooper; Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, 2004; 23: 145–52.

- The Second Tower of Babel: Ana Castillo's Borgesian Precursors in The Mixquiahuala Letters By: Jirón-King, Shimberlee; Philological Quarterly, 2003 Fall; 82 (4): 419–40.

- Creating a Resistant Chicana Aesthetic: The Queer Performativity of Ana Castillo's So Far from God By: Mills, Fiona; CLA Journal, 2003 Mar; 46 (3): 312–36.

- The Homoerotic Tease and Lesbian Identity in Ana Castillo's Work By: Gómez-Vega, Ibis; Crítica Hispánica, 2003; 25 (1–2): 65–84.

- Ana Castillo's So Far from God: Intimations of the Absurd By: Manríquez, B. J.; College Literature, 2002 Spring; 29 (2): 37–49.

- Hybrid Latina Identities: Critical Positioning In-Between Two Cultures By: Mujcinovic, Fatima; Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, 2001 Spring; 13 (1): 45–59.

- Con un pie a cada lado'/With a Foot in Each Place: Mestizaje as Transnational Feminisms in Ana Castillo's So Far from God By: Gillman, Laura; Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, 2001; 2 (1): 158–75.

- La Llorona and a Call for Environmental Justice in the Borderlands: Ana Castillo's So Far from God By: Cook, Barbara J.; Northwest Review, 2001; 39 (2): 124–33.

- Chicana/o Fiction from Resistance to Contestation: The Role of Creation in Ana Castillo's So Far from God By: Rodriguez, Ralph E.; MELUS, 2000 Summer; 25 (2): 63–82.

- Rebellion and Tradition in Ana Castillo's So Far from God and Sylvia López-Medina's Cantora By: Sirias, Silvio; MELUS, 2000 Summer; 25 (2): 83–100.

- Gritos desde la Frontera: Ana Castillo, Sandra Cisneros, and Postmodernism By: Mermann-Jozwiak, Elisabeth; MELUS, 2000 Summer; 25 (2): 101–18.

- Chicana Feminist Narratives and the Politics of the Self By: Elenes, C. Alejandra; Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 2000; 21 (3): 105–23.

- 'Saint-Making' in Ana Castillo's So Far from God: Medieval Mysticism as Precedent for an Authoritative Chicana Spirituality By: Sauer, Michelle M.; Mester, 2000; 29: 72–91.

- Shea, Renee H. "No Silence for This Dreamer: The Stories of Ana Castillo." Poets & Writers 28.2 (Mar.-Apr. 2000): 32–39. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Edu. Jeffrey W. Hunter. Vol. 151. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002. Literature Resource Center. Web. 12. Sept. 2013.

Book articles/chapters

[edit]- Determined to Indeterminacy: Pan-American and European Dimensions of the Mestizaje Concept in Ana Castillo's Sapogonia By: Köhler, Angelika. IN: Bottalico and Moncef bin Khalifa, Borderline Identities in Chicano Culture. Venice, Italy: Mazzanti; 2006. pp. 101–14

- Ana Castillo (1953–) By: Castillo, Debra A.. IN: West-Durán, Herrera-Sobek and Salgado, Latino and Latina Writers, I: Introductory Essays, Chicano and Chicana Authors; II: Cuban and Cuban American Authors, Dominican and Other Authors, Puerto Rican Authors. New York, NY: Scribner's; 2004. pp. 173–93

- The Spirit of a People: The Politicization of Spirituality in Julia Alvarez's In the Time of the Butterflies, Ntozake Shange's sassafrass, cypress & indigo, and Ana Castillo's So Far from God By: Blackford, Holly. IN: Groover, Things of the Spirit: Women Writers Constructing Spirituality. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame P; 2004. pp. 224–55

- 'A Question of Faith': An Interview with Ana Castillo By: Kracht, Katharine. IN: Alonso Gallo, Voces de América/American Voices: Entrevistas a escritores americanos/Interviews with American Writers. Cádiz, Spain: Aduana Vieja; 2004. pp. 623–38

- A Chicana Hagiography for the Twenty-first Century By: Alcalá, Rita Cano. IN: Gaspar de Alba, Velvet Barrios: Popular Culture & Chicana/o Sexualities. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2003. pp. 3–15

- Ana Castillo as Santera: Reconstructing Popular Religious Praxis By: Pérez, Gail. IN: Pilar Aquino, Machado and Rodríguez, A Reader in Latina Feminist Theology: Religion and Justice. Austin, TX: U of Texas P; 2002. pp. 53–79

- A Two-Headed Freak and a Bad Wife Search for Home: Border Crossing in Nisei Daughter and The Mixquiahuala Letters By: Cooper, Janet. IN: Benito and Manzanas, Literature and Ethnicity in the Cultural Borderlands. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi; 2002. pp. 159–73

Books

[edit]- New Visions of Community in Contemporary American Fiction: Tan, Kingsolver, Castillo, Morrison By: Michael, Magali Cornier. Iowa City: U of Iowa P; 2006.

- Exploding the Western: Myths of Empire on the Postmodern Frontier By: Spurgeon, Sara L.. College Station, TX: Texas A&M UP; 2005.

- Ana Castillo By: Spurgeon, Sara L.. Boise: Boise State U; 2004.

- Contemporary American Fiction Writers: An A-Z Guide. Edited by Champion, Laurie and Rhonda Austin Westport: Greenwood, 2002.

- Vivancos Perez, Ricardo F. doi:10.1057/9781137343581 Radical Chicana Poetics. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Chabram-Dernersesian, Angie (2006). The Chicana/o Cultural Studies Reader. London/New York: Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 0415235154.

- ^ Aviles, E. (2018). Contemporary U.S. Latinx literature in Spanish : straddling identities. Michele Shaul, Kathryn Quinn-Sánchez, Amrita Das. Cham, Switzerland. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-3-030-02598-4. OCLC 1076485572.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Sapogonia (Novel 1990) | Ana Castillo". Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Notable Books of the Year 1993". The New York Times. December 5, 1993. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Bio | Ana Castillo". Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "PREVIOUS WINNERS OF THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARD" (PDF). beforecolumbusfoundation.com. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Bio – Ana Castillo – anacastillo.com". Archived from the original on September 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Manríquez, B.J. "Ana Castillo". The American Mosaic: The Latin American Experience. ABC-CLIO. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Hampton, Janet Jones (January–February 2000). Américas. 52 (1): 48–53.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ a b c d Shea, Renee H. "No Silence for This Dreamer: The Stories of Ana Castillo." Poets & Writers 28.2 (Mar.-Apr. 2000): 32–39. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Edu. Jeffrey W. Hunter. Vol. 151. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002. Literature Resource Center. Web. 12. Sept. 2013.

- ^ a b c d Calafell, Bernadette Marie. "Ana Castillo". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515600-3. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Juffer, Jane. "On Ana Castillo's Poetry". Modern American Poetry.

- ^ Saeta, Elsa (1997). "A MELUS Interview: Ana Castillo". MELUS. 22 (3): 133–149. doi:10.2307/467659. JSTOR 467659.

- ^ Herrera, Cristina (2011). "Chicana Feminism". Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World. SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781412995962. ISBN 9781412976855. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Castillo, Ana. Ana Castillo. 2013. http://www.anacastillo.com/content/. September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Guide to Ana Castillo's Papers". University of California – Santa Barbara. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Castillo, Ana (2008). The Guardians. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780812975710.

- ^ Herrera, Spencer (2008). "World Literature In Review". World Literature Today. 82: 63. JSTOR 40159683 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Gonzalez-Barrera, Ana (November 19, 2015). "More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S." Pew Research Center's Hispanic Trends Project. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Szeghi, Tereza M. (2018). "Literary Didacticism and Collective Human Rights in US Borderlands: Ana Castillo's The Guardians and Louise Erdrich's The Round House". Western American Literature. 52 (4): 403–433. doi:10.1353/wal.2018.0001. ISSN 1948-7142. S2CID 165340959.

- ^ GONZÁLEZ, YAATSIL GUEVARA (2018). "Navigating with Coyotes: Pathways of Central American Migrants in Mexico's Southern Borders". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 676: 174–193. doi:10.1177/0002716217750574. ISSN 0002-7162. JSTOR 26582305. S2CID 148918775.

- ^ Committee, Mexico-U.S. Border Program and Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project of the American Friends Service (1996). "Border Fatalities: The Human Costs of a Militarized Border". Race, Poverty & the Environment. 6/7: 30–33. ISSN 1532-2874. JSTOR 41495626.

- ^ Hidalgo, Javier (September 1, 2016). "The ethics of people smuggling". Journal of Global Ethics. 12 (3): 311–326. doi:10.1080/17449626.2016.1245676. ISSN 1744-9626. S2CID 152109548.

- ^ Wright, Melissa W. (2011). "Necropolitics, Narcopolitics, and Femicide: Gendered Violence on the Mexico-U.S. Border". Signs. 36 (3): 707–731. doi:10.1086/657496. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 10.1086/657496. PMID 21919274. S2CID 23461864.

- ^ Falcón, Sylvanna (2001). "Rape as a Weapon of War: Advancing Human Rights for Women at the U.S.-Mexico Border". Social Justice. 28 (2 (84)): 31–50. ISSN 1043-1578. JSTOR 29768074.

- ^ Pérez-Torres, Rafael (1998). "Chicano Ethnicity, Cultural Hybridity, and the Mestizo Voice". American Literature. 70 (1): 153–176. doi:10.2307/2902459. ISSN 0002-9831. JSTOR 2902459.

- ^ "Preguntas for Ana Castillo". Front Porch. May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Queirós, Carlos J. "An Interview With Ana Castillo --AARP VIVA". AARP. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official site

- Ana Castillo Poetry Foundation biography and poetry podcast

- Comprehensive interview with Ana Castillo published in Fifth Wednesday Journal Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Voices from the Gaps biography

- Guide to the Ana Castillo papers at the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives

- Modern American Poetry

- Esta puente, mi espalda: Voces de mujeres tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos (co-translator & co-editor, 1988). San Francisco: ism press. ISBN 978-0-910383-19-6 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-910383-20-2 (hardcover)

- 20th-century American novelists

- American poets of Mexican descent

- American women short story writers

- Writers from Chicago

- American feminist writers

- Living people

- University of Chicago alumni

- Northeastern Illinois University alumni

- 1953 births

- Hispanic and Latino American novelists

- American postmodern writers

- Chicana feminists

- 21st-century American novelists

- American women poets

- American women essayists

- American women novelists

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- 20th-century American poets

- 21st-century American poets

- Lambda Literary Award winners

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 21st-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American essayists

- 21st-century American essayists