Republic of Austria v. Altmann

| Republic of Austria v. Altmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued February 24, 2004 Decided June 7, 2004 | |

| Full case name | Republic of Austria et al. v. Altmann |

| Citations | 541 U.S. 677 (more) 124 S. Ct. 2240; 159 L. Ed. 2d 1; 2004 U.S. LEXIS 4030 |

| Case history | |

| Prior |

|

| Subsequent | |

| Holding | |

| The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act applies retroactively. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Stevens, joined by O'Connor, Scalia, Souter, Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Concurrence | Scalia |

| Concurrence | Breyer, joined by Souter |

| Dissent | Kennedy, joined by Rehnquist, Thomas |

Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, or FSIA, applies retroactively to acts prior to its enactment in 1976.[1]

Decision

[edit]The case turned on the "anti-retroactivity doctrine", which is a doctrine that holds that courts should not construe a statute to apply retroactively (to apply to situations that arose before it was enacted) unless there is a clear statutory intent that it should do so. This means that, regarding lawsuits filed after its enactment, the FSIA standards of sovereign immunity and its exceptions apply even to conduct that took place before 1976. Since the intent of FSIA was the codification of already existing well settled standards of international law, Austria was deemed not immune from litigation, for acts that first arose from criminal conduct during World War II.

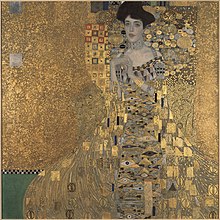

The result of this case for the plaintiff, Maria Altmann, was that she was authorized to proceed with a civil action against Austria in a U.S. federal district court for recovery of five paintings stolen by the Nazis from her relatives and then housed in an Austrian government museum. As the Supreme Court noted in its decision, Altmann had already tried suing the museum before in Austria, but was forced to voluntarily dismiss her case because of Austria's rule that court costs are proportional to the amount in controversy (in this case, the enormous monetary value of the paintings). Under Austrian law, the filing fee for such a lawsuit is determined as a percentage of the recoverable amount. At the time, the five paintings were estimated to be worth approximately US$135 million, making the filing fee over US$1.5 million. Although the Austrian courts later reduced this amount to $350,000, this was still too much for Altmann, and she dropped her case in the Austrian court system.

The high court remanded the case for trial in the Los Angeles district court. Back in the district court, both parties agreed to arbitration in Austria in 2005, which in turn ruled in favor of Altmann on 16 January 2006.

Case

[edit]Adele Bloch-Bauer, the subject of two of the paintings, had written in her last will: "Meine 2 Porträts und 4 Landschaften von Gustav Klimt, bitte ich meinen Ehegatten nach seinem Tode der österr. Staats-Galerie in Wien zu hinterlassen"; that is, "I ask my husband to bequeath my 2 portraits and the 4 landscapes by Gustav Klimt to the Austrian State Gallery in Vienna after his death." Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer signed a statement acknowledging Adele's wish in her last will. He also donated one of the landscape paintings to the Belvedere Gallery in Vienna in 1936.[2] The Austrian arbitration determined that Adele was probably never the legal owner of the paintings. Rather, it viewed it as more likely that Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer was their legal owner and that in turn his heirs, including Altmann, were the rightful owners.

Aftermath

[edit]Reactions and auction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

The ruling in favor of Maria Altmann came as a great shock to the Austrian public and the government.[citation needed] The loss of the paintings was regarded in Austria as a loss of national treasure.[3] She had attempted earlier to come to some mutual agreement in 1999; however, the government repeatedly ignored her proposals.[3] Maria Altmann told the government that the time was up and there would be no deal from her side anymore.[citation needed] The Austrian government declined to accept a condition of the arbitration which would have allowed it preferentially to purchase the paintings at an attested market price.[citation needed] The paintings left Austria in March 2006 and were returned to Altmann.[3] Consequently, the Austrian government received criticism from the opposition parties for its failure to secure a deal with Altmann at an earlier stage.[3] The city of Vienna also asserted that buying back the paintings was a "moral duty".[3]

Just months after the Austrian government finally returned Ms. Altmann's family's heirlooms to her, she consigned the Klimts to the auction house Christie's, to be sold on her behalf. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I sold for allegedly $135 million in a private sale, the others in auction, e.g. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II for $88 million, with the five paintings fetching a total of over $327 million.[4]

Gallery of the Klimts

[edit]-

Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912

-

Buchenwald/

Birkenwald, 1903 -

Apfelbaum I, 1912

-

Häuser in Unterach am Attersee, 1916

Documentaries

[edit]Maria Altmann's story has been recounted in three documentary films. Stealing Klimt, which was released in 2007, featured interviews with Altmann and others who were closely involved with the story. Adele's Wish[5] by filmmaker Terrence Turner, who is the husband of Altmann's great-niece, was released in 2008, and features interviews with Altmann, her lawyer, E. Randol Schoenberg, and leading experts from around the world. The piece was also featured in the 2006 documentary The Rape of Europa, which dealt with the massive theft of art in Europe by the Nazi Government during World War II.

Dramatization

[edit]Altmann is portrayed by Helen Mirren, and Schoenberg by Ryan Reynolds in the film Woman in Gold, chronicling Altmann's nearly decade-long struggle to recover the Klimt paintings. The film was released on April 3, 2015.

See also

[edit]- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 541

- Art repatriation

- National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism

- Alperin v. Vatican Bank

- Woman in Gold (film)

References

[edit]- ^ Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004).

- ^ http://www.adele.at/Klage_von__Dr__Stefan_Gulner_m/Vorgelegte_Urkunden/Testament_vom_19_1_1923_von_Ad/testament_vom_19_1_1923_von_ad.html Archived 2011-05-31 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ a b c d e "Museum threatened, takes down Klimt paintings". Ynetnews.com. European Jewish Press. January 1, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Christopher Michaud, Christie's stages record art sale, Reuter's, November 9, 2006. Accessed November 9, 2006.

- ^ Adele's Wish

Sources

[edit]- Czernin, Hubertus (2006), Die Fälschung: Der Fall Bloch-Bauer und das Werk Gustav Klimts (in German), Vienna: Czernin Verlag, ISBN 3-7076-0000-9.

External links

[edit]- Text of Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004) is available from: Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- Adele's Wish Documentary film on the Republic of Austria v. Altmann court case

- National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism

- Institute for the History of Jews in Austria

- Holocaust Victims' Information and Support Center

- Republic of Austria | Historikerkommission